treatment preferences for particular interventions

[23– 25,27,32,35,44,52,53] .Aside from recruiter influences,

patient preferences can be informed by a number of factors,

including information and advice from family and friends

[25]and the media

[25]. Mills and colleagues

[41]conducted an analysis of audio recordings of recruitment

appointments with 93 participants in a trial of localised

prostate cancer treatments. Patient preferences ranged

from hesitant opinions to well-formed intentions to receive

a particular treatment. These preferences frequently

changed after detailed discussion of treatments and trial

rationale with recruitment staff. However, several studies

have highlighted that recruiters can feel uncomfortable

exploring these further

[24,32,40,44,52]and are more likely

to accept patient preferences if they align with the

recruiter’s own views

[27,28].

3.2.7.

Identifying specific recruitment issues in RCTs

Whilst the challenges identified are commonly reported

across a range of RCTs, it is important to note that the degree

that these issues are present and the extent that they affect

recruitment will inevitably vary between RCTs. For in-

stance, whilst recruiters often struggle to feel comfortable

with the concept of uncertainty between trial arms, training

and support strategies can sometimes help overcome this so

that recruitment targets are met

[25]. In other instances, the

lack of recruiter equipoise has been so fundamental that the

RCT had to be closed

[32] .In addition to these common themes, each RCT will have

a set of unique issues that need to be resolved

[50] .Urologi-

cal RCTs often involve complicated pathways that can be

particularly lengthy, and include many different healthcare

professionals or multiple centres

[44] .The availability and

evidence base for treatment options outside of each RCT will

vary (particularly within fields such as urology, where there

are rapidly changing treatment options

[23]), which may

have implications for clinician equipoise. Some RCTs may

also have complex designs, making them even more

difficult to discuss with patients. For instance, recruiters

from one urological trial had to explain the need for

neoadjuvant chemotherapy, the timing of randomisation in

relation to the cycles of chemotherapy, and two extremely

different treatment arms (surgery to remove the cancer and

bladder, or a selective bladder preservation technique that

involved radiotherapy to destroy the cancer and preserve

the bladder except where the tumour persisted when

surgery was recommended)

[44].

3.3.

Part 2: what solutions are there to recruitment difficulties?

3.3.1.

Developing training programmes for those recruiting to trials

Taken together, the previous section has highlighted the

need for training and support for recruiters (both for generic

and RCT-specific issues). Only a relatively small number of

studies have used qualitative research to develop training

for those recruiting patients into RCTs

[24,26,31,32,38,44, 50,52] .One study developed a peer-review training

programme, whereby four research nurses from an

orthopaedic pilot study provided regular feedback on each

other’s recorded RCT consultations. All the nurses felt that

communication and recruitment abilities were improved,

and stated that they would want to repeat this process in

subsequent trials

[38].

The other interventions identified had originated from

the ProtecT study

[4_TD$DIFF]

, whereby a complex intervention was

developed to improve rates of randomisation and informed

consent

[25].

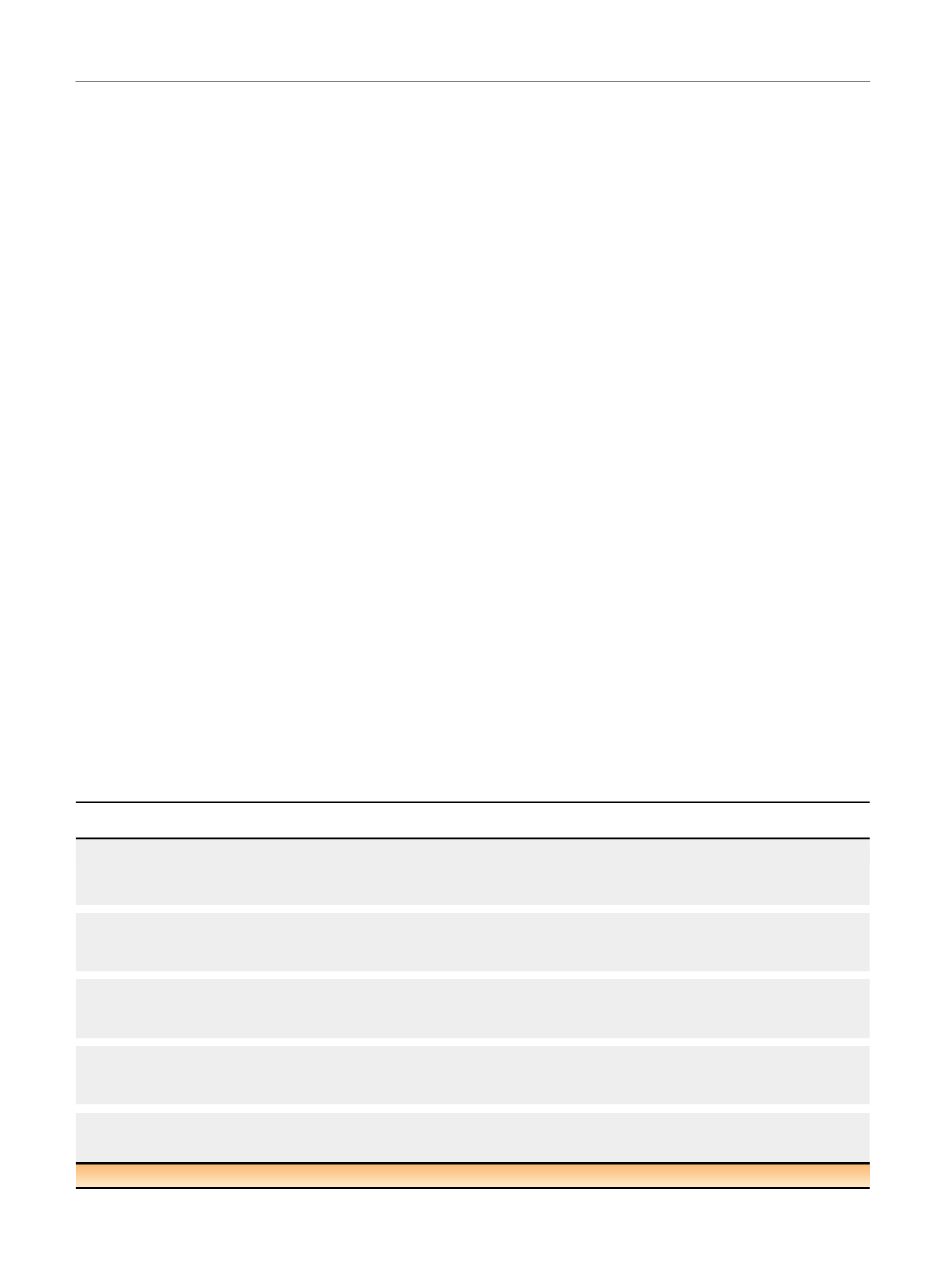

Table 3summarises the key issues identified

and strategies implemented to overcome these. This

intervention has since been refined in a number of RCTs

[24,26,31,32,44,50,52] ,and the final version of the QuinteT

Recruitment Intervention (QRI) is conducted in two phases.

Phase 1 aims to understand the trial recruitment process by

Table 3 – Issues identified in the ProtecT study and strategies to improve recruitment

[25]1. Organisation and presentation of study information

Treatments tended to be presented in a standard order: surgery, radiotherapy, and then active monitoring. Analysis showed that these options were not

presented equally. Recruiters were asked to present the treatments in a different order [(1) active monitoring, (2) surgery, and (3) radiotherapy] and to

describe their advantages and disadvantages.

2. Terminology used in study information

The term ‘‘trial’’ was sometimes interpreted as monitoring (‘‘try and see’’), so recruiters were asked to use ‘‘study’’ instead. Recruiters had tried to reassure

patients that there was a good 10-yr survival (‘‘the majority of men with prostate cancer will be alive 10 yr later’’). However, patients interpreted this to

suggest that they might die in 10 yr. It was recommended that recruiters present survival in terms of ‘‘most men with prostate cancer live long lives’’.

3. Specification and presentation of the nonradical arm

Recruiters often called the non-radical arm ‘‘watchful waiting,’’ but patients had interpreted this as ‘‘no treatment’’, where the disease would be

watched and the patient waited for death (‘‘watch while I die’’). This was renamed ‘‘active monitoring’’ and redefined to involve three monthly or six

monthly prostate specific antigen tests, with intervention if required or requested.

4. Presentation of randomisation and equipoise

Both recruiters and patients had difficulty with randomisation and equipoise. Recruiters were supported to feel comfortable discussing uncertainty

and explaining that patients were suitable for all three treatments. They were also advised to explain the rationale for randomisation and explain that

if the patient were uncertain, randomisation represented a way of resolving the dilemma of treatment choice.

5. Exploring patient preferences

Recruiters initially felt uncomfortable discussing patient preferences. Training emphasised that it was important to elicit and explore preferences,

particularly if these were not well founded in evidence (eg, rejecting radiotherapy because of a mistaken belief that it would lead to hair loss).

ProtecT = Prostate Testing for Cancer and Treatment trial.

E U R O P E A N U R O L O G Y 7 2 ( 2 0 1 7 ) 7 8 9 – 7 9 8

794