DE-EBRT increased from 71% to 86%

( Fig. 1 ). Patients with

intermediate and high risk experienced a similar decline in

the proportion receiving LDR-B, and the interaction

between risk group and year had no effect on LDR-B boost

treatment selection (

p

= 0.2).

3.3.

Survival analysis

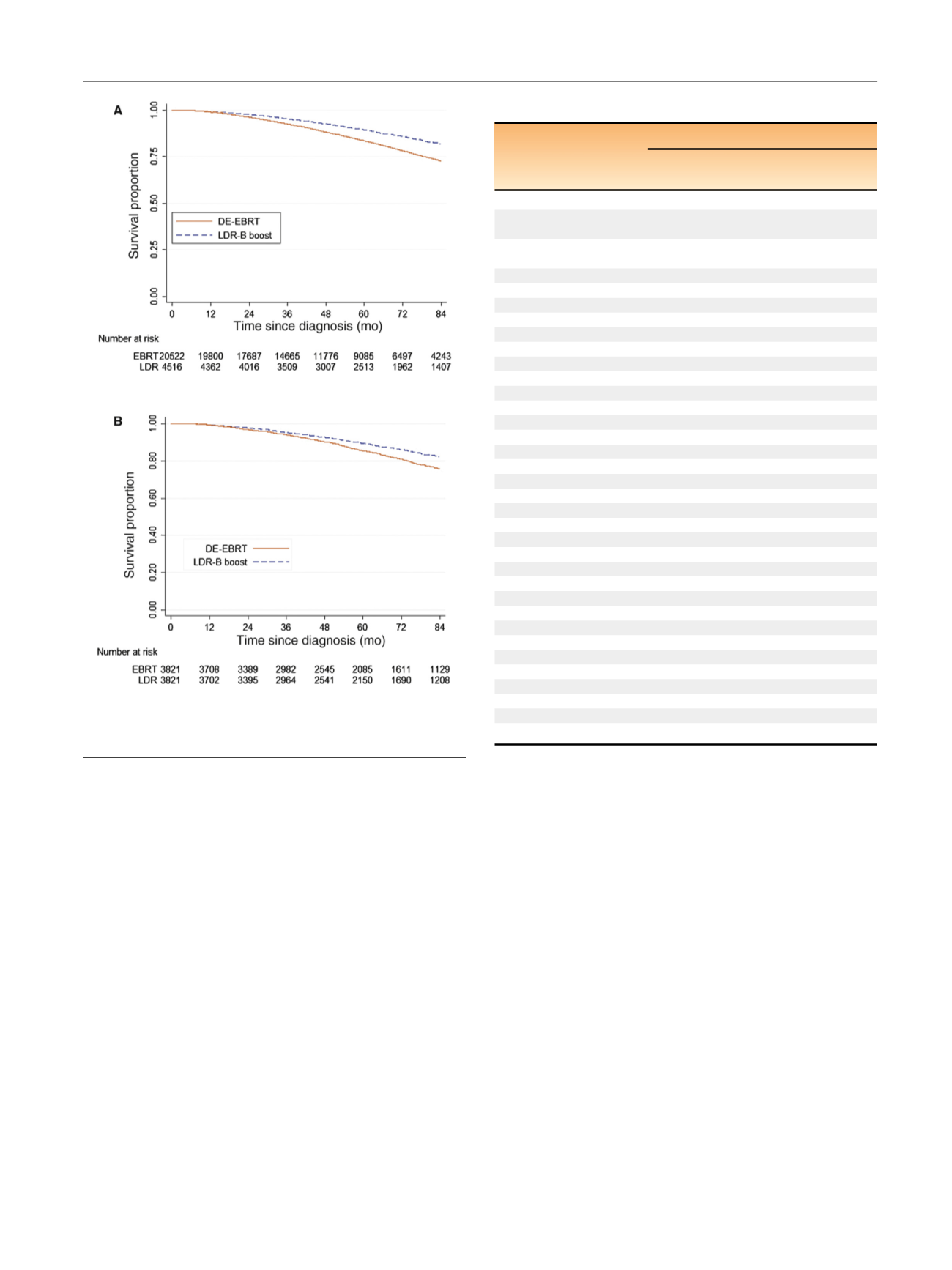

On UVA, LDR-B boost was associated with better (hazard

ratio [HR] 0.63, 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.58–0.68;

p

<

0.001) when compared to DE-EBRT. The 7-yr OS was

82%for LDR-B boost and 73% for the DE-EBRT group

( Fig. 2 A). On MVA, LDR-B boost remained independently

associated with better OS (HR 0.70, 95% CI 0.64–0.77). Other

significant variables associated with OS on UVA and MVA

are shown in

Table 2.

3.4.

Propensity score matching

Propensity score matching identified a cohort of

7642 patients without significant differences in matching

factors found to be associated with treatment selection

(Supplementary Table 2). Of these, 3821 received LDR-B

boost, and 3821 received EBRT alone. Comparison of

propensity score–matched samples confirmed better OS

associated with LDR-B boost (HR 0.74, 95% CI 0.66–0.89;

7-yr OS 82% vs 76%;

Fig. 2B). On sensitivity analysis, the

difference between DE-EBRT and LDR-B boost remained

until 80% of DE-EBRT patients with GS 7 disease were

artificially increased to GS 8–10.

3.5.

Subset analyses

When limiting the analysis to those younger than 60 yr with

no comorbidities to approximate PCa deaths, the benefit of

LDR-B boost persisted, with 7-yr OS of 90% compared to 85%

for DE-EBRT (log-rank

p

<

0.001;

Fig. 3 ). For all patients,

there was no interaction between treatment and age

(

p

= 0.92), treatment and risk group (

p

= 0.82), treatment

and dose (

p

= 0.66), or risk group and dose (

p

= 0.86).

4.

Discussion

Our findings suggest that men with unfavorable-risk PCa

who were selected to undergo LDR-B boost survived longer

Table 2 – Overall survival analyses from 2004 to 2012

Variable

Hazard ratio (95% confidence interval)

Univariate

analysis

Multivariate

analysis

Treatment

External-beam

radiation therapy

Reference

Reference

Low-dose rate

brachytherapy

0.63 (0.58–0.68)

0.70 (0.64–0.77)

Age (continuous)

1.05 (1.05–1.06)

1.05 (1.04–1.05)

Race

Black

Reference

Reference

Non-Hispanic white

1.14 (1.05–1.24)

1.00 (0.91–1.10)

Other

0.73 (0.55–0.96)

0.68 (0.50–0.92)

Insurance

Medicare

Reference

Reference

Uninsured

0.50 (0.35–0.71)

0.84 (0.57–1.26)

Private

0.57 (0.53–0.62)

0.92 (0.84–1.01)

Medicaid

0.95 (0.78–1.15)

1.57 (1.26–1.97)

Government/unknown 0.92 (0.78–1.09)

1.18 (0.98–1.43)

Geographic region

Northeast

Reference

Reference

South

1.06 (0.98–1.15)

1.07 (0.99–1.17)

Midwest

1.15 (1.06–1.24)

1.09 (1.00–1.19)

West

1.01 (0.92–1.11)

0.97 (0.88–1.08)

Facility type

Academic

Reference

Reference

Nonacademic

1.10 (1.03–1.18)

1.13 (1.04–1.22)

Charlson comorbidity score

0

Reference

Reference

1

1.38 (1.27–1.51)

1.44 (1.31–1.58)

2+

2.56 (2.21–2.96)

2.50 (2.13–2.95)

Gleason score

6

Reference

Reference

7

1.11 (0.99–1.25)

1.15 (1.01–1.31)

8–10

1.58 (1.41–1.77)

1.50 (1.32–1.70)

PSA (continuous)

1.001 (1.001–1.002)

1.002 (1.001–1.002)

Clinical stage

T1c–T2a

Reference

Reference

T2b–T2c

1.25 (1.17–1.34)

1.21 (1.13–1.30)

T3a

1.34 (1.16–1.55)

1.25 (1.07–1.46)

[(Fig._2)TD$FIG]

Fig. 2 – (A) Unadjusted and (B) propensity-matched Kaplan-Meier

survival curves by either dose-escalated external beam radiation

therapy (DE-EBRT) or low-dose-rate brachytherapy (LDR-B) boost.

E U R O P E A N U R O L O G Y 7 2 ( 2 0 1 7 ) 7 3 8 – 7 4 4

741