[47]

.

[47]

.

The group receiving the combination including

nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAID) experienced

a greater reduction in nocturia (–1.5 0.9 vs –1.1 0.9,

p

= 0.034), but with a higher incidence of gastrointestinal side

effects. Gastric discomfort with loxoprofen was seen in 12.5%,

as compared with 2.6% of the control group.

3.4.3.

Phytotherapy

An 8-wk placebo-controlled RCT looked at SagaPro (Saga-

Medica, Reykjavik, Iceland), a product derived from

Angelica

archangelica

leaf, in 69 men with 2 nocturnal voids (LoE

1b)

[48]. The study found no significant difference between

the treatment groups, except on post-hoc subgroup

analysis. In a crossover trial of furosemide and gosha-

jinki-gan, 36 patients were reported to have improved

symptom score, quality of life, nocturnal frequency, and

hours of undisturbed sleep with both medications (LoE 2b)

[49] .3.4.4.

Agents to promote sleep

A crossover RCT of 20men with bladder outflow obstruction

and nocturia (mean 3.1/night) compared 2 mg melatonin

with placebo (LoE 1b)

[50]. Melatonin and placebo caused a

decrease in nocturia of 0.32 and 0.05 episodes/night

(

p

= 0.07). Nocturia responder rates (a mean reduction of

at least –0.5 episodes/night) were higher with active

medication (

p

= 0.04). Daytime urinary frequency and IPSS

were minimally altered.

3.4.5.

Summary of medical therapy of nocturia in men

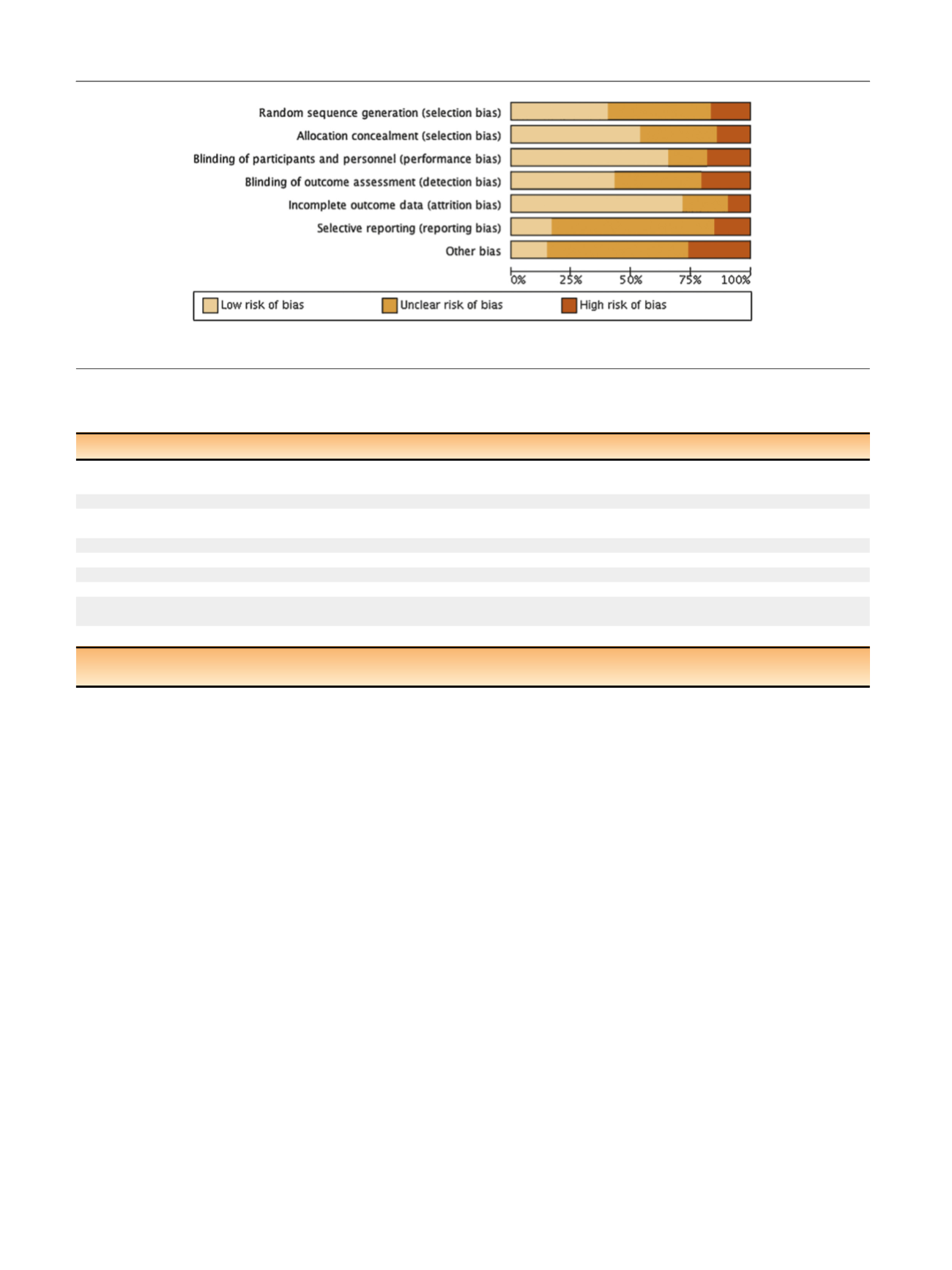

A summary of the effect of medical therapy, excluding

antidiuretic, on nocturia is given in

Table 5. Risk of bias

summary for all treatments is given in

Figure 2, and a table

for individual studies is given in Supplementary data.

Recommendations from the European Association of

Urology Guidelines panel for Nonneurogenic Male LUTS

are given in

Table 6.

4.

Conclusions

A detailed review of principal medical therapies of nocturia

has been presented. It assumes that conservative measures

are addressed as part of the care package. The nature of the

reports included reflects the importance of several influ-

ences; the use of subjective or objective markers as primary

outcomes, the range of severity included (twice per night

being a commonly applied threshold), and the importance

of subjective ‘‘bother.’’ The differences apparent in pub-

lished literature in regards to populations, definitions, study

design, outcome measures, and treatment durations repre-

sent a substantial limitation for the evidence base of

nocturia therapy. In nocturia, some trials report an

Table 6 – European Association of Urology Guidelines Panel for Non-neurogenic Male Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms (LUTS)

recommendations on medication treatment of nocturia in men

LE GR

Treatment should aim to address underlying causative factors, which may be behavioral, systemic condition(s), sleep disorders, lower urinary

tract dysfunction, or a combination of factors

4

A aLifestyle changes to reduce nocturnal urine volume and episodes of nocturia, and improve sleep quality should be discussed with the patient

3

A aDesmopressin may be prescribed to decrease nocturia in men under the age of 65 yr. Screening for hyponatremia must be undertaken at

baseline, during dose titration and during treatment

1a

A

a

-1 adrenergic antagonists may be offered to men with nocturia associated with lower urinary tract symptoms

1b B

Antimuscarinic drugs may be offered to men with nocturia associated with overactive bladder

1b B

5

a

-Reductase inhibitors may be offered to men with nocturia who have moderate-to-severe LUTS and an enlarged prostate (

>

40 ml)

1b C

PDE5 inhibitors should not be offered for the treatment of nocturia

1b B

A trial of timed diuretic therapy may be offered to men with nocturia due to nocturnal polyuria. Screening for hyponatremia should be

undertaken at baseline and during treatment

1b C

Agents to promote sleep may be used to aid return to sleep in men with nocturia

2

C

GR = grade; LE = level of evidence; PDE5 = phosphodiesterase type 5.

a

Upgraded based on panel consensus.

[(Fig._2)TD$FIG]

Fig. 2 – Risk of bias.

E U R O P E A N U R O L O G Y 7 2 ( 2 0 1 7 ) 7 5 7 – 7 6 9

766